In 1900, Providence had five professional theaters, Infantry Hall, Music Hall, and the amateur Talma Theater. By 1915, there were thirteen theaters in downtown Providence alone, plus three or four new neighborhood movie houses in Olneyville Square and on Federal Hill. No less than nineteen theaters existed downtown during the seventeen years from 1902 to 1919, and fourteen opened in that period.

Roger Brett, Temples of Illusion p.165

A couple of years ago I was searching out a suitable venue to hold a performance Providence’s central arts district. It was surprisingly difficult to come up with something that fit my needs as an aspiring promoter; venues were either too private, or too big, or too formal, or too commercial. It seemed like there was always some reason why Providence lacked the right spaces.

When I began thinking about abandoning ship, I let go of my attachment to the present challenges, and started thinking about Providence at the turn of the 20th century. Could understanding the history of vaudeville theatre help me approach the venue problem from a different angle?

Between the 1870s and the 1920s, Providence’s downcity district exploded with purpose-built, often opulent, vaudeville halls. It was the heady days prior to the First World War; the days before white flight gutted the city center, and, perhaps most significantly, the days before I95 bisected the city like a crude wedge. Rhode Island’s capital was a live entertainment hub, rivaling New York to the South and Boston to the North in terms of theatres per capita.

Why of all the seasons, the Spring of 1917? The period jumped out at me because it was eminently transitional. On the national stage, The Zimmerman Telegram was revealed to the American public and the Selective Service Act passed in Congress. These events shaped the psychological contours of a public eager for sentimental distractions and fantastic spectacles, of which there were plenty to be found on vaudeville stages.

1917 also saw the rise of the low-cost movie house, an institution that began to eat up a growing chunk of the theatre-going public’s time and money. Shifting material resources and centralization of theatre syndicates (such as BF Keith’s) accompanied the industrial changes that would shepherd vaudeville theatres into cinemas where one could view early silent photoplays, and later mid-century talkies.

In the Fay Theatre scrapbooks, which reside in the collection of The Rhode Island Historical Society, clippings from the Providence Journals of the day noted some extraordinary milestones in the local scene during the Spring of 1917: French chanteuse Sarah Bernhardt performed in Providence for her fourth and final time, Harry Houdini staged a death-defying escape after being bound and submerged in the Providence River, and Emery’s Majestic, home today to The Trinity Repertory Company, opened its doors on Washington Street.

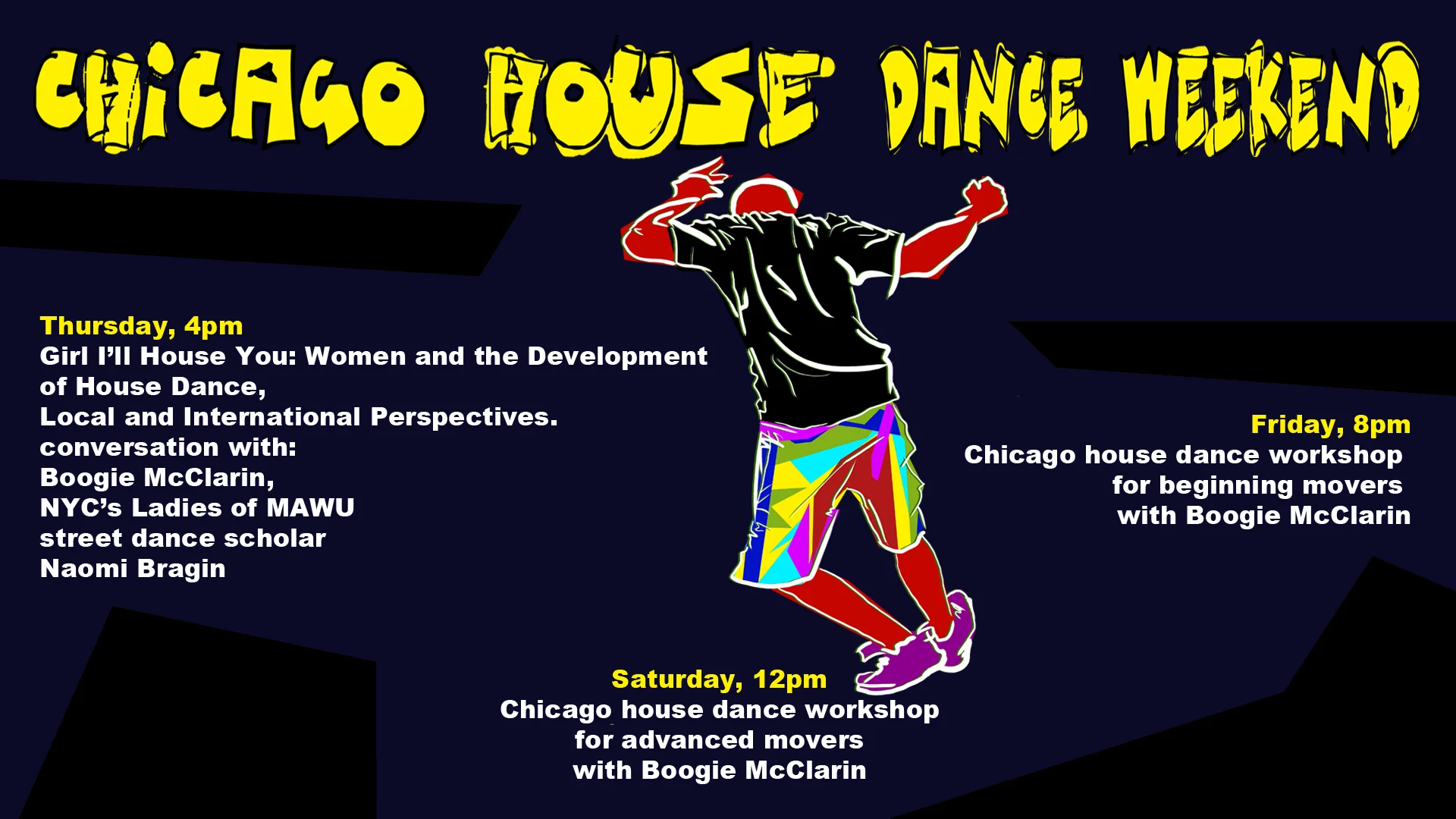

To share this history with a wide public, I looked to graphic ephemera from the day: elaborate, often hand-drawn illustrations from Sunday Providence Journal advertisements for the various theatres of note. These spoke to me as the artifacts of Providence’s DIY poster culture, the visual antecedents of today’s wheat-pasted and silk-screened broadsides.

The performance/music heritage that these advertisements evoke inspired me to create a series of soundwalks. The six tours, designed to be listened to in the vaudeville sites themselves while walking, are partly personal, replete with my own real memories of live music in downcity Providence, and partly guided tours of the vaudeville era’s spatial history. While the archive is delimited by time, I have made a great effort to include information about diachronous sites of import in Providence’s vaudville history, not just those relating to the Spring of 1917.

Many thanks are due to the staff of The Rhode Island Historical Society’s Providence Branch, the Cinema Treasures online community and Roger Brett, who’s indispensible Temples of Illusion proved to be the most concise and well-researched secondary source on Providence vaudeville. I am similarly indebted to RIGenWeb, who’s scanned Sanborn Fire Map from 1918 grounded my spatial understanding of downtown Providence, Brown’s Center for Digital Scholarship, and the helpful librarians at the John Hay Library.

I hope you will find this archive as generative as I have, and welcome your comments and ideas.